Kent Coast Sea Fishing Compendium |

Bait |

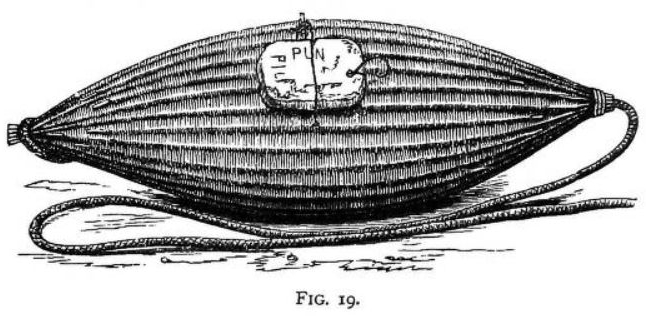

Sitting still and wishing

|

Introduction

| E | Excellent |

| G | Good |

| V | Variable |

| Hermit Crab | Harbour Ragworm | King Ragworm | Lugworm | Mackerel | Mussel | Prawn | Peeler Crab | Razorfish | Sandeel | Squid | Silver Ragworm | |

| Bass | V | G | G | V | G | E | E | E | V | E | ||

| Cod | V | V | E | V | V | V | E | E | G | E | ||

| Conger | E | G | G | |||||||||

| Dab | V | E | E | E | E | G | V | E | ||||

| Flounder | V | E | E | E | V | E | E | V | E | |||

| Garfish | E | E | G | |||||||||

| Gurnard | V | V | G | V | E | G | G | E | ||||

| Mackerel | E | E | G | |||||||||

| Mullet | E | |||||||||||

| Plaice | V | E | E | V | E | E | E | V | V | E | ||

| Pollack | G | E | G | G | ||||||||

| Scad | E | G | V | |||||||||

| Whiting | G | E | E | G | V | E | E | E | G | G | E | |

| Wrasse | G | G | E | G | V | E | E | V | E |

Angling in Salt Water: A Practical Work on Sea Fishing with Rod and Line from the Shore, Piers, Jetties, Rocks and from Boats (1887) John Bickerdyke at page 43

The sea angler should bear in mind that mussels, cheap oysters, cockles, and shrimps are often to be obtained at the shell fish shops beloved of the working classes. Herring, mackerel, and sprat, we may find at the fishmonger's. For live shrimps we must go to the shrimpers, but may be able to obtain both them and prawns ourselves with a shrimp net worked over the sand and among the rocks. For that most valuable bait, the squid, we must board the trawlers on their arrival, and this usually means rising very early. Fisher boys will generally dig lugs in the shore and ragworms in the harbour mud for a consideration.

"Sea-Fishing on the English Coast" (1891) Frederick George Aflalo at pages 43, 44 & 49

Chapter IV

Baits and Diary

Natural Baits

… I think the most concise way of putting the reader in possession of the various natural baits for sea-fish will be to give a list in their order of precedence as general baits (i.e. leaving all local baits, or those that are attractive to one species only, till last), and to place opposite each the fish most likely to take it, also in order of precedence. Remember the first eight of these, as they are particularly good all-round baits, and there are few fish that will take none of them.

| 1 | Lugworm | whiting, pout, flat fish |

| 2 | Mussel | smelt, pout, flat fish, codling |

| 3 | Squid | bass, conger, whiting |

| 4 | Sand-eel | pollack, bass, conger |

| 5 | Fresh Herring | bass, conger, whiting |

| 6 | Pilchard | conger, cod, bass, whiting |

| 7 | Ragworm | chad, pollack, mullet, smelt |

| 8 | Mackerel | mackerel, bass, conger |

| 9 | Shrimps | bass, pollack, flat fish, pouting |

| 10 | Prawns | pollack, bass |

| 11 | Hermit Crab | flat fish, pout, chad |

| 12 | Green Crab | bass, gurnard, mullet |

| 13 | Cockle | codling, whiting |

| 14 | Whelk | cod, codling, whiting |

| 15 | Limpet | pout, chad, gurnard |

| 16 | Sprat | cod, whiting, ling, haddock |

| 17 | Bloater | conger, bass |

| 18 | Dab's Head | bass |

| 19 | Oyster Beards | codling, cod, whiting |

| 20 | Skate's Liver | mullet, bass |

| 21 | Soft Roe of Herring | mullet, pout, smelt |

| 22 | Silkweed | mullet |

| 23 | Smelt | smelt, whiting |

| 24 | Sea-Anemone | flat fish, smelt |

| 25 | Lobster | flat fish, smelt |

"The Sea and the Rod" (1892) Deputy Surgeon-General Charles Thomas Paske & Frederick George Aflalo at page 150

Chapter XVII

Concerning Baits

The writer [1] of a book on sea-fishing, published in 1801, gives a good general rule for determining the most effective bait at any time or place: "Open the belly of the first fish you catch, and note its contents."

[1] The Art of Angling, Rock, and Sea Fishing: with the Natural History of River, Pond, and Sea-Fish (1740) Richard Brookes at pages 12 and 22:

"If you are in doubt at any time about a proper bait, it will be a good way when you have taken a fish to slit his gills, and take out his stomach, and observe carefully what he last fed upon … Baits. To know, at any time, what bait fish are apt to take, open the belly of the first fish you catch, and take out his stomach very tenderly; open it with a sharp penknife, and you will discover what he then feeds on."

First published in 1740 this popular book was reworked for the rest of the 18th century, reaching at least nine editions by 1801. Richard Brookes, M.D., (1721 - 1763) was an "industrious compiler" and among his translations from the French was "A Natural History of Chocolate" (1724) from the French "Histoire Naturelle du Cacao et du Sucre" (1719). As a "compiler" Brookes was ordinarily reliant on the work of others for much of his material, if not his actual text, and identifies two of his principal sources for the "Art of Angling": Mr Ray and "Willoughby's Historia Piscium" (for the illustrations) and Mr. Chetwood for large swathes of the text ("In the Angling Part I had the Assistance of Mr. Chetwood, who is allow'd by all to have great skill in that innocent diversion, and therefore most of the egotisms in the First Part, or where the sentence is usher'd in with I, have him for their author, as well as some other things which are here and there interspers'd among the directions for angling"). Brookes' account is weighted more towards natural history than techniques for capturing fish, some of which he describes are of a sort only incidentally caught by commercial fishermen such as the "porpuss", hammerhead shark and "sea serpent":

"The Sea-Serpent is commonly about five feet long. The body is exactly round, slender, and of an equal thickness, except towards the tail, where it grows sensibly more slender. The colour of the upper half is of a dusky yellow, like the dark side of old parchment or vellum; the lower part is of a brightish blue. The snout is long, slender, and sharp, and the mouth opens enormously wide. The flesh is very well tasted and delicate, but is full of very small bones, and therefore cannot be eaten without some trouble. It is taken very frequently in the Mediterranean."

"The Sea and the Rod" (1892) Deputy Surgeon-General Charles Thomas Paske & Frederick George Aflalo at page 182

Chapter XVIII

Summary of Useful Hints

III. Let all baits be perfectly fresh. Neither be too lavish nor too sparing with your bait; fishermen pride themselves on their courteous treatment of one another. Never hesitate to try a new bait; its absence from any book is the fault of the writer, and no condemnation of the bait itself. Always, where practicable, use ground-bait.

"Hints and Wrinkles on Sea Fishing" (1894) "Ichthyosaurus" (A. Baines & Frederick George Aflalo) at pages 45 & 46

Natural History and Sport

The natural food of fish is more difficult to discover, owing to the rapidity with which they masticate and digest it. To this the shark family are an exception, and the person who cuts open a fresh-caught shark is generally fortunate enough to find within it half a dozen haddock, a couple of good-sized cod, and maybe a human leg or a sheep, only partially decayed. I have taken seven large mackerel from the stomach of a dogfish … The problem is rendered the more complicated from the fact that this natural food of fish varies with different seasons and with different localities. Some fish follow their favourite food from place to place, whereas others, more philosophical and less energetic, accustom themselves to some other handier dish. Thus, the cod come after the sprats, and the pollack after the sand eels, but when sprats and sand eels have all gone, down their throats or elsewhere, then are cod well content with lugworm, and pollack are unable to resist the lively ragworm.

"The Badminton Library: Modern Sea Fishing" (1895) John Bickerdyke at pages 79, 80, 132, 133, 200 & 201

Baits

… in any town in which there is a merchant in shell fish, or, in less grandiose language, a whelk shop, there bait is likely to be obtained - first-rate mussels, large and luscious; delicate little cockles; periwinkles; and sometimes limpets; while for the long line which requires a good tough bait there are the whelks. In not a few places the proprietors of these useful establishments, having of late years been patronised by anglers in salt water, very sensibly also keep a small supply of lug and rag worms; the first mentioned being one of the best possible baits for ground-feeding fish, though odious to use. My advice then is, when visiting new regions, hunt up the shell-fish shop (it will probably be down a side street in a more or less slummy neighbourhood), and see what that will bring forth. Even if mussels, and whelks, and the commoner kinds of bivalves are not procurable, we can throw thrift to the winds and utilise cheap oysters as baits for our hooks; some of the large and high-flavoured members of this family which come from foreign parts are fit for little else. It should also be remembered that sea fish are fond of the beards of oysters.

For lugworms and ragworms we must go to the sands and muddy estuaries. Where much line fishing takes place, the lads are practised in the art of catching these objectionable-looking baits, and will keep up a daily supply for a small consideration; but if there be neither sands, nor mud, nor shell-fish shops, then, unless we import worms from more favoured localities, we must, if mussels also fail us, seek mackerel, sprat, herring, or pilchard at the fishmonger's. He may perhaps have some grey gurnard, and will most surely be able to supply us with sole-skin with which to make small baits for bass and other fish. Almost any bright, shining skin which is sufficiently tough may be used for this purpose. Smelts, too, are to be had at the fishmonger's, and these are serviceable on the bottom for whiting and cod, besides making very good spinning baits for bass or pollack. If there any trawlers about they will generally bring home in the early morning some squid or cuttlefish; but these curious creatures are so plentiful on some parts of our coast that they can be easily caught by means of a bait …

Thanks to the liberality of gentlemen living at Plymouth, experiments, which were continued for some time, were made under the auspices of the Marine Biological Association with the object of discovering some chemically prepared bait for sea fish. Those who know the difficulty there often is in obtaining a few baits for a day's fishing with the paternoster, can well understand that professional fishermen, who deal with thousands of hooks and miles of line, must be from time to time seriously hampered by want of bait. For while there is often a great abundance of sprats, pilchard, herring and mackerel, in some seasons next to nothing is to be obtained suitable for the purpose. It was thought possible an oily extract of pilchard could be produced, with which some substance in common use and easily procurable could be flavoured. It can hardly be said that any success attended the experiments. The extract was certainly made, but no substance has yet been discovered which, when flavoured with it, will keep on the hooks and be acceptable to fish. Possibly some angler of the future will make the discovery; for sea anglers are not less ingenious than other members of the craft. One medium which I suggested to the then director of the M.B.A. was macaroni. If the hollow centre could be filled with the extract of squid or pilchard and the ends sealed, the whole would be permeated with the strong-smelling liquid. From the mullet-fishing experience … it seems that at least one sea fish favours this bait even without the essence. If a quasi-artificial bait of this nature can be discovered, the fishermen will benefit to the extent of many thousands pounds annually.

Artificial Baits

Those who possess the least ingenuity need never be at a loss for a bait for sea fishing, or, at least, for so many of the sea fish as will take an artificial bait. A piece of white rag on a hook, the stem of a tobacco pipe threaded on the shank, a three-penny-bit hammered out with a hole bored in it, a teaspoon or dessert spoon bowl bored with a hole and decorated with a hook or two, a piece of tin from a sardine box cut to the shape of a fish and given a twist to make it spin, a piece of india-rubber band or tubing, a few feathers and wool from an old rug these and many more simple and easily obtained materials can be made up into killing sea-fish baits. The things that anglers should never be without are hooks and leads of various weights, swivels, gut, and gimp. With these, he ought to be able to make almost any tackle he may require, perhaps not so neatly as that which he can buy, but certainly more lasting. Not that I wish to disparage bought tackle, though the fastenings-off are not always the best, and hooks not always tested. But in outlandish places, hundreds of miles from tackle-shops, the exercise of a little ingenuity and trouble on the part of the angler will often make all the difference between a good day's fishing and a bad one, between a full and an empty creel.

From Land and Pier

Sea fishing does not only consist of personal skill. Success depends in a great measure on your fishing at the right time and in the right place, with the right baits. These three things are all important; but above all use your own brains, and if you are not catching fish try to puzzle out the reason for your failure … There was an old and very successful fisherman who was once asked what he used that enabled him to fill his creel so fully and frequently, and he replied, "Brains".

"Modern Sea Angling" (1921) Francis Dyke Holcombe at page 9

Introductory

As many a sea angler knows from unhappy personal experience, the matter of bait is often a veritable thorn in the flesh to him, for it sometimes happens that none of the usual baits is obtainable. In such cases the novice may be counselled to display a little resource and initiative, and try experiments. Even if he catches no fish he will be no worse off than if he stayed ashore bemoaning his fate. Two examples may be given. On one occasion a sea angler, confronted with the "no bait" difficulty, gathered some garden snails, with which he went afloat. With the snails he caught pouting, some of which he cut up and used as bait to catch other fish. The other instance occurred many years ago at Ballycotton … The men in question went to sea one day with no bait, and apparently no possibility of obtaining any, but overcame the difficulty by putting over a piece of bread on a small hook. With this they caught a whiting, and with pieces of the whiting many more of his brethren. Anchoring on different ground, they got among the hake with whiting bait and made a great catch. Many of the hake, on being hauled on board, vomited up herrings, so that in the end the fishermen had plenty of bait - both whiting and herring. The moral of experiences such as these would seem to be that lack of any of the ordinary baits need not necessarily cause the sea angler to despair.

"Sea Fishing Simplified" (1929) Francis Dyke Holcombe & A. Fraser-Brunner at page 15

Chapter II

It is a sound general rule in all sea fishing that, under normal conditions, the bigger the bait the larger the fish caught - within reasonable limits, of course. It is also a rule of equal - perhaps of greater - importance, that if the water be very clear and bright the size of the bait used should be reduced, while you should also employ finer tackle than you would if the water was coloured a little. Very thick water is not an advantage, for the fish cannot see the bait so well.

"Sea Fishing Baits: How to Find & Use Them" (1957) Alan Young at pages 78 to 90

CHAPTER X

FISH FOODS AND BAITS

The following list is not exhaustive and is intended only as a general guide. Food differs with locality and season, and it is best to offer, where there is a choice, the food likely to be found in the place concerned at the time, but if this proves unsuccessful, try any other baits available.

The diet of several species is made up largely of plankton (very small floating plant and animal life) and by creatures too small or too soft to be of use as bait. These have been ignored. Squid, where mentioned, applies equally to cuttlefish and octopus.

ANGLER FISH

Food. Live fish of any species.

Bait. The angler fish is not an angler's fish, but it will take almost any large bait that passes near its mouth.

BASS

Food. Small bass: prawns; shrimps; hoppers; brit. Large bass: crabs; sand eels; prawns; any fish small enough to be swallowed; worms. Some large and very large bass seem to be habitual bottom feeders.

Bait. Small bass: prawns; shrimps; slaters; strips of fish; small brit; pieces of worms. Large bass: crabs (peeler or hard-back, whole); sand eels; prawns; small fish; hermit crabs; fish liver; lugworms; ragworms; squid; sand-hoppers. The habitual bottom feeders will take any bait, even if far from fresh.

BREAM, BLACK

Food. Seaweed (probably for the minute organisms living in it); worms; and small shellfish.

Bait. Ragworm; pieces of fish.

BREAM, RED

Food. Shellfish; small fish.

Bait. Pieces of herring, mackerel or pilchard; crab meat; worms.

BRILL

Food. Small fish, especially sand eels, sprats and brit.

Bait. Sand eels and any small fish. Many brill have been caught on lugworms.

COALFISH

As for pollack.

COD

Food. A cod will eat anything eatable, alive or dead.

Bait. Every standard bait is likely to be taken by cod, but mussels are particularly successful.

CONGER

Food. Fish, squid, all species of crab.

Bait. Fish, from sprat to herring size. Fillets from larger fish. Whole squid. Herrings and mackerel are good, but conger bait must be fresh, and a fresh-caught pouting or whiting, for example, is likely to be a better bait than a slightly stale herring bought from a fishmonger.

DABS

Food. Very small crabs of all species, including hermit crabs; sand-hoppers; mussels; and any creature likely to be found in sand or mud.

Bait. As food, and ragworm and lugworm.

DOGFISH

Food. The spur dog is in the main a fish eater. The smooth hound and the lesser spotted dogfish live mainly on hermit and other crabs; molluscs such as whelks; sand eels; worms; and other bottom-dwelling creatures. The larger spotted dogfish mixes these two diets, eating both fish and shellfish. All will attack wounded fish and are thus responsible for seizing hooked whiting, etc.

Bait. Fish; pieces of fish; crabs, especially hermit crabs; whelks.

FLOUNDERS

Food. Flounders take a wide variety of foods, but shore crabs; shrimps; cockles; worms; and fish, such as sand eels, brit and sprats, are important.

Bait. The foods mentioned above vary with geographical locality, the specific locality (estuary or sea), and the season. It is best to start with a bait that ought to be right for time and place. When a flounder is caught it should be opened up to see what it has been eating. Flounders will take almost any bait presented on a baited spoon.

GARFISH

Food. Brit and sand eels.

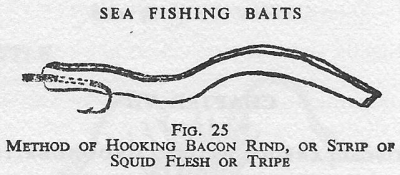

Bait. Brit; lasts; sand eels and imitations of sand eels, such as bacon rind or tripe strips.

GURNARD

Food. Gurnards obtain their food by scratching the sea bed with their claw-like pectoral fins. It varies with the nature of the bottom, but sand shrimps and very small crabs of any species predominate.

Bait. Gurnard will take almost any small bait.

HADDOCK

Food. Mainly crustaceans and shellfish - shrimps; all species of crabs; many species of tube worms; razor fish; whelks. A few small fish.

Bait. Hungry haddocks will take almost anything - even a bare shining hook. In other circumstances mussel is an almost infallible bait.

HAKE

Food. The hake is a mid-water fish, preying mainly on species of whiting and squid offshore, and on young hake in the open sea; and on pelagic species, such as herring, pilchards and mackerel in shallower waters.

Bait. Small whole fish and fillets of fish.

HALIBUT

Food. Fish of practically every species; haddock and whiting predominating. Very large halibut take big skate and cod. Some shellfish taken, particularly hermit crabs, especially by small halibut.

Bait. Whole fish, generally of about herring size.

HERRING

Food. Mainly a plankton feeder.

Bait. Herring are caught from dock walls and jetties, usually by night. Small pieces of ragworm are a standard bait.

JOHN DORY

Food. Small fish, shrimps, prawns, swimming ragworms. Almost any creature that swims freely.

Bait. Brit, ragworm, prawn.

LING

Food. Fish. A ling will feed at any level, so there are very few species of small fish not recorded as forming part of its diet.

Bait. Whole fish up to herring size or fillets of larger fish. Mackerel, herring, pilchards and whiting are the best.

MACKEREL

Food. On leaving the spawning grounds in very early spring mackerel feed only on plankton. Later they take all upper-water species, particularly brit and sand eels.

Bait. Lasts, sand eels, small strips of bacon, squid and tripe. Any small shining bait is likely to be successful when a school of feeding mackerel is found.

MONKFISH

Note. Squatina squatina, known also as the angel ray. It looks somewhat like the rays, and is a link between rays and dogfish. It is not the angler fish, though the latter is frequently called the monkfish, especially by longshoremen.

Food. Fish, with occasional crabs. Normally a bottom feeder, flatfish form a large part of the diet, but monkfish will sometimes feed at higher levels.

Bait. Not specially fished for. It is likely to take any bait.

MULLET, GREY

Food. In natural conditions the grey mullet is thought to exist in the main upon filamentous weed and the innumerable arthropods - varying from miscroscopic to pea size - such weeds contain. Unnatural conditions have been created by man, and since weed of the right sort grows on piles, jetties, harbour walls, buoys, etc., grey mullet have become frequenters of harbours. There they find a wide variety of unnatural foods and it appears that they will eat - or at least take into their mouths - almost any form of small rubbish. They browse among the kitchen scraps thrown out by ships, and frequent any place where fish offal is discarded. Michael Kennedy (The Sea Angler's Fishes) says: "In Kilmore Quay, in Wexford, I have seen grey mullet, in shoals, poking about among the carcases of rays dumped in the harbour, and sucking in the odd shreds of liver left in them."

Bait. It is almost impossible to lay down a bait for mullet. They have been caught on small scraps of nearly every bait mentioned in this book; and on green harbour weed; bread; and a lengthy list of odd items, including woodlice and cubes of banana. They can be seen in clear water ignoring a dozen baits of a substance on which they were feeding avidly the day before, and taking some freak bait displayed in the middle of them. Almost every fishing station has its locally accepted mullet bait, and it is probable that over the years it proves the best average bait - but when on any occasion it obviously fails, the angler should try anything. A large mullet was caught on a cigarette end. Grey mullet penetrate far up the estuaries and are often caught by freshwater anglers using paste, earthworms or maggots.

MULLET, RED

Apart from their names there is no connection between grey and red mullets. All the details under gurnards, including the habit of scratching the sea bed, applies to red mullet.

PLAICE

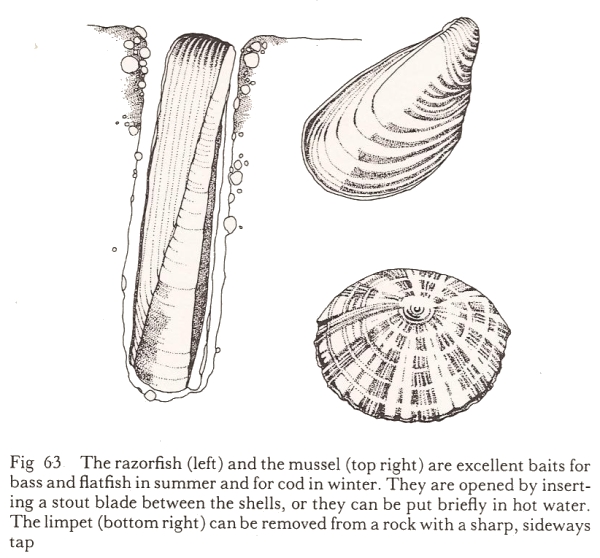

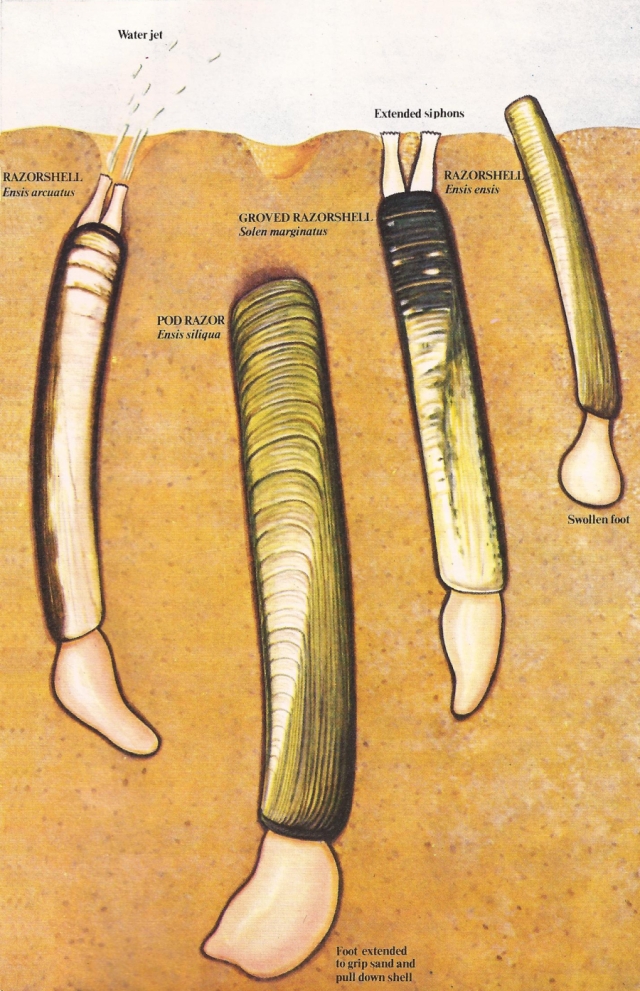

Food. The plaice is such an important food fish that scientists have devoted much study to it, and a description of its food occupies several pages of an official report. Boiling this down to a line or two, it can be said that plaice of takeable size (10 in. and over) feed almost exclusively on shell-fish, particularly razor-fish; trough shells; tellins; and wedge shells.

Bait. Some of the shellfish mentioned are deep-water species. The angler cannot do better than use razor-fish and cockles, the latter being a close approach to two of the deep-water species. Plaice in shallow water will often take lugworm and ragworm.

POLLACK and COALFISH

Food. Pollack are predacious fish that live for preference among weed-covered rocks. They will eat any type of worm or crab, but their principal food is brit, sand eels, sprats and other small fish.

Bait. Live or dead sand eels and other fish; fillets of fish; worms; crabs. A pollack takes a moving bait more readily than a still one, and is thus particularly susceptible to artificial lures.

POUTING

Food. Worms; small crabs (especially hermit); and various shellfish.

Bait. Lugworm; ragworm; small crabs and crab meat; winkles; mussels.

RAYS. See SKATE

SCAD (HORSE MACKEREL)

As for mackerel.

SHAD

The allis and twaite shads enter rivers to spawn between April and June. Very few anglers fish for them specifically and little is known about their food. A considerable number are caught every season, usually on brit or sand eels, or on baits or lures imitating these fish.

SHARKS

Shark angling is a specialized sport. Blue sharks are the principal quarry, and almost any species of fish will serve as bait providing it is quite fresh. Mackerel and pilchards are commonly used, but whiting, pollack, pouting, etc., have all proved successful. Mako sharks are usually caught by anglers fishing for blue sharks. Thresher sharks are occasionally caught by anglers, but are not fished for deliberately. They have taken fish baits.

SKATES AND RAYS

There is no scientific distinction between skates and rays. There are more than a dozen British species, but most are caught by accident. Anglers fish deliberately for only two species, the common skate and the thornback skate (or thornback ray).

SKATE, COMMON

Food. Many species of fish, including common skate, dogfish and flatfish; crabs and lobsters; squid. Small skate also feed on shrimps; worms; and shellfish.

Bait. A small whole fish, a fillet from a large fish, or a squid or piece of squid for large skate. Pieces of fish; crabs; and worms for small skate.

SKATE, THORNBACK

Food. Crabs, especially hermit crabs; shrimps; shellfish, especially razor-fish; and a few sand-dwelling fish, such as sand eels and flatfish.

Bait. Crabs and crab meat; sand eels; shellfish.

SOLES

Food. Worms of all kinds, particularly ragworms; shrimps; razor-fish; and, locally, brittle starfish. A night feeder.

Bait. Ragworms and other worms.

TOPE

Food. Fish of any size the tope can seize.

Bait. Fresh fish - notably mackerel; pilchards; pouting; whiting.

TURBOT

Food. Almost exclusively a fish eater.

Bait. Sand eels; brit; sprats.

WHITING

Food. Unlike most other fish of the cod family, the whiting usually chases its food and does not search the sea bed. Main food is fish - brit and the young of any species, including its own.

Bait. Pieces of fish; small fish; occasionally worms. When sprats are in, whiting are unlikely to take other baits.

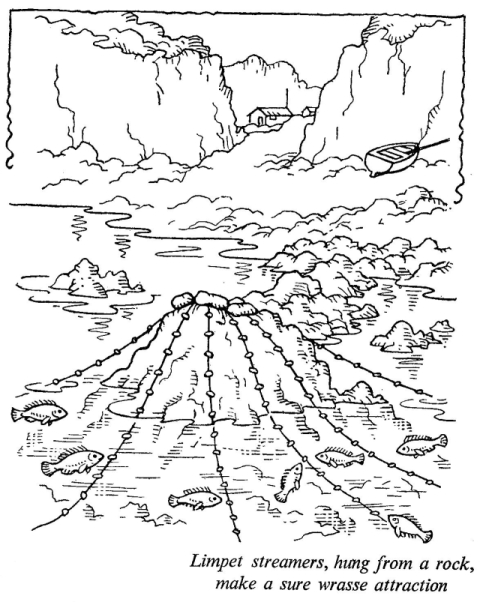

WRASSE

Food. All species of crabs and most shellfish; prawns.

Bait. Prawns; small crabs and crab meat; any shellfish; worms, including earthworms.

"The Sea Angler Afloat and Ashore" (1965) Desmond Brennan at pages xiv & xix

Introduction

The secret of successful angling is to fish in the right place, at the right time, with the right lure and the right tackle. The right place is where the fish are most likely to feed under the prevailing conditions of season and weather. The right time is the state of tide or weather or the time of day when the fish are most likely to feed. The right bait or lure is their natural food at the time or an acceptable alternative. The right tackle is that which will most easily and effectively present the bait in an acceptable manner to the fish, hook the fish when it takes, and handle the fish when hooked. Where there are a variety of suitable methods the one which gives the most sport to the angler is the one which should be used.

The angler's primary concern, therefore, is to present to the fish something that it will accept as, or mistake for, food and to do so in the way most likely to attract the fish's attention at a time that it is likely to be feeding. His secondary concern is to avoid frightening the fish. This, in many instances, is just as much of importance as a frightened fish will not take.

The right method is the one which will enable the angler to present his bait or lure in the most natural way or in a manner likely to deceive the fish. Thus, spinning with artificial lures may be the best method to take shoaling bass, whilst a bottom bait fished just behind the surf would be the answer on a beach. The methods used will vary with the species and with the conditions under which the fishing is done. The angler must be familiar with all the different methods and techniques used and to be able to adapt his methods to suit conditions. If one method fails he should try another; he should be willing to experiment and to learn. He should always think about his fishing and he should never fish by rule of thumb. Fish may not be intelligent but there is no reason why the angler should not be.

"Successful Sea Angling" (1971) David Carl Forbes at page 47

The perfect bait, viewed by a fish, looks as though it could be eaten, and moves as though it should be eaten. Regardless of the lure or bait involved, the main deterrent to its success might be not that it looks unnatural, but rather that it is presented on tackle which makes it react unnaturally in the water. Within limits, rather than worry overmuch about the type of bait, it would seem better to concentrate on how to present that bait.

"The Bait Book" (1979) Ted Lamb at page 176

35 Containers for Sea Baits

The sea angler should take care to avoid using any metal containers for bait. Sea water reacts strongly with metal, creating poisonous and corrosive chemicals which, if they do not kill the bait outright, will at least taint it and make it unpleasant for fish. This leaves the angler with the choice of inert plastics or wood.

Two Hundred Sea Fishing Tips (1982) Ivan & Ivor Garey Tip 74

11. Natural Bait

74. Tinned bait - forget it !

We'll tell you how to get rich quick: discover a method for preserving sea bait without loss of efficiency. To date no-one has been able to do so. We dutifully try out every preserved bait that comes on the market, but the results are always negative. Deep-frozen bait occasionally yields results, but so far as catches are concerned nothing has yet been discovered to beat fresh bait. And what is more, the fresher the better. We must therefore regretfully advise you not to waste your money on preserved bait of any kind. If we should ever discover an effective type of preserved bait we promise you that our shouts of joy will be heard all over Europe.

Lugworm

Common lugworm ("blow lug") are widely used as bait, probably because they make a good hookful of material that is acceptable to a wide range of fish. Also, they are comparatively easy to find and dig from shores of sand and muddy sand. Lugworms occur both on the open coast and in sheltered bays and estuaries (e.g. Pegwell and Sandwich Bays).

Black lugworm are found on moderately exposed sandy shores but do not seem to live in estuaries where blow lug may be abundant. Unlike blow lug they only occur below mid-tide level and live in more or less vertical burrows up to one metre in depth.

The tail-less lugworm is found on stony or gravelly ground. Fish which feed on these worms are thus accustomed to finding one or other species in most intertidal areas.

"Genetic evidence for two species of lugworm (Arenicola) in South Wales" P. S. Cadman & A. Nelson-Smith (1990)

Field observations suggest that the common lugworm Arenicola marina (L.) has two forms on British shores although taxonomists have hitherto mostly recognised it only as a single species showing some morphological variation. Using gel electrophoresis of enzyme systems in homogenised tissue from specimens collected around Swansea (South Wales, UK), we have shown that the 2 forms do not appear to share the same gene pool. The 2 forms are fixed for different alleles at 3 loci out of the 6 which proved to be consistently resolvable and show little similarity in the 2 variable loci at which alleles are shared. Only 4 alleles were found to be common out of 22 investigated. A high value for Nei's Genetic Distance (1.3032) and a low one for Genetic Identity (0.2717) also indicate that they are separate species. An observed heterozygote deficiency is probably due to the mixing of populations as a result of the extended pelagic dispersal phase of larvae and post-larvae.

Editor's Note 1: In their subsequent paper "A new species of lugworm Arenicola defodiens" sp. nov. J.Mar.Biol.Ass.UK. 73(1) 213-224 published in 1993, P. S. Cadman and and A. Nelson Smith confirmed that the 'blacklug' (which appears to prefer the bottom of more exposed sandy shores) as described by anglers was a new species (Arenicola defodiens). In summary, the common names for Arenicola marina are blow lug, lobworm and yellowtail and for Arenicola defodiens are black lug or runnydown.

Editor's Note 2: See Sea Fishing (1911) Charles Owen Minchin at pages 253 & 254:

The most popular of all baits, both with most fishes and most fishermen, is the lug-worm, which rejoices in the rather pretty scientific name of Arenicola marina. There are two races or varieties: the common brown kind, which is abundant on every sandy shore in Western Europe, and a darker, tougher and much larger sort, which is called laminary, because its habitat is near the low-water mark. This is not found everywhere, but can be obtained on some of the Lancashire shores, in the Channel Islands, and several other places. It grows to 16 in long … The large black variety seems to make a deep straight burrow which does not curve back to the surface.

| Phylum | Family | Common & scientific names |

Summary of life history and ecology |

| Polychaeta (Bristle worms) | Nereidae, Ragworms | Harbour rag Hediste (Nereis) diversicolor King rag Neanthes (Nereis) virens Ragworm Perinereis cultrifera |

Free-living, omnivorous, fast-growing worms which breed only once in their lifecycle before dying. They are farmed commercially for bait. Sexes are separate, and all mature worms spawn on the same day. Some mature after one year, but wild king ragworms are usually two or three years old at maturity. Usually one third or more of the population breeds each year and recruitment to the population is rapid. Some populations have much larger, older worms. These reproduce slowly and are more vulnerable to over-collection. |

| Nephtyidae, Catworms or silver rag | Nephtys caeca, Nephtys cirrosa, Nephtys hombergi | Catworms actively swim and burrow in clean sand beaches in search of prey. They are long-lived, have separate sexes, and may breed several times in a lifetime. All mature worms in a population breed on the same day, but not always every year. Larvae spend up to 5 weeks in the plankton before settling onto the bottom. An average 3 inch worm is usually 4-5 years old. The largest may be up to 12 years old. Large worms are highly valued by match anglers. Their slow growth, infrequent spawning and low recruitment rates make them vulnerable to over-collection. Research into farming is underway. | |

| Arenicolidae, Lugworms | Blow lug, Lobworm or Yellowtail Arenicola marina Black lug or Runnydown Arenicola defodiens |

Lugworms live in U or J-shaped burrows on sandy and muddy sand shores and in the sub-littoral, and feed on decaying seaweed, diatoms and bacteria. Sand casts are left above one burrow entrance. They begin to breed and are large enough for bait at 2 years old, and may live for 6 years reaching weights of 10g (north-east England) to 25g (south and west). They breed several times during their life. Each worm spawns in a day, and all worms on a beach spawn within a few days, but those on different beaches spawn at different times. Some worms die after spawning. Others stop feeding and casting until their larvae leave the adult burrow to spend 6 months below the low water mark. They then swim to upper shore juvenile lugworm beds. Maturing worms move down the shore to adult beds. This life cycle makes most lugworm populations able to recover quickly from over-digging. Both species should soon be available from bait farms. | |

| Guidelines for managing the collection of bait and other shoreline animals within UK European marine sites (December 1999) S. L. Fowler | |||

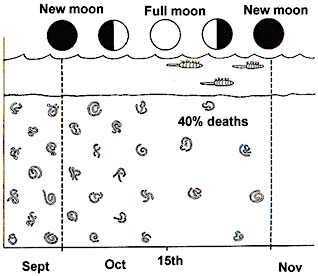

Lugworms leave their burrows twice a year to spawn and, when they do so, are vulnerable to fish predation. The lugworm releases eggs and sperm from within the safety of its burrow between spring tides in late October. At this time deaths following spawning can reduce the numbers of lugworm on a beach by as much as 40% and for a short time, many dead worms may be found on the surface of the sand.

Lugworms also migrate by a form of swimming, which takes place at times not associated with spawning. Swimming worms have been seen in May, when bare stretches of beach may be quickly re-colonised. It seems probable that fish are especially attracted to lugworm beds, both below and between the tidemarks, in May and in October-November. At these times they may even be conditioned to, or preoccupied with, feeding on these worms.

Lugworms are the classic winter cod bait and there are occasions when fish won't look at anything else. Lug is effective for most species, but whiting and flatfish show a particular liking. Black lug is regarded as superior to blow for cod. Lugworm is often best cocktailed with another bait. Indeed strategic tipping lug with the likes of mackerel, squid, clam, mussel or peeler crab can prevent worms slipping and clogging the hook, so long as elastic thread is used to whip the bait firmly in place.

Bait slippage is not so pronounced with tougher fresh black lug, and more often applies to frozen blacks and softer blow lugworms. There is always debate about whether to hook lugworms head first or tail first. When hooking multiple smaller lugworms to form a large bait, I don't think it matters. However, when hooking just one or two blows, or a single big black lug always put the hook in tail first, so that the point exits through the juiciest part of the worm.

When lugworms are in good supply there is no need to fridge them, but in the depth of winter, when supplies are unpredictable, then lugworms dug in better weather or during the more productive spring tides can be kept for a week. Lugworms will keep alive and reasonably fresh for up to a week in dry newspaper. For longer periods they can be "tanked" in seawater, although this is said to wash the worms out and make them less effective as bait. However, they remain a better bait than no worms at all.

Common lugworms are best wrapped in packets of 20 (a score) in a minimum of three layers of newspaper, but beware placing packets on top of each other. An alternative is to place them in a cat litter tray in a dribble of seawater; this also applies to live yellowtails.

Don't submerge worms because this allows bacteria to spread quickly and dead worms to kill live ones. The worms don't have to swim, just be kept wet.

Tougher yellowtails or black lugworms can also be wrapped in newspaper, although they are more often placed in "rolls" of ten. Double over a single sheet of newspaper and place the worms at intervals in the paper as you roll it up, then wrap rolls in scores.

"Sea Fish & How to Catch Them" (1863) William Barry Lord at page 77

Worms

Lug worms … are obtained by digging with a spade in the sand at low water, where the sand-heaps show their workings.

"Sea-fishing as a sport" (1865) Lambton J. H. Young at pages 58, 59, 61 & 62

Baits

The Lug-Worm. The lug, or lurgan, is a worm of a peculiar and, indeed, disgusting appearance, but at the same time is eagerly devoured by almost all fish, especially young codlings and flat-fish. These worms are found in the mud-banks of most estuaries, where their whereabouts is easily discovered by sundry casts near the hole they inhabit. They are found by digging for them with a very strong kind of prong … in the fisheries, at about half-tide mark, or else with the hands in the soft mud uncovered at low tide. The usual mode is to turn up the shirt-sleeves to the shoulders and the trousers above the knees, when, having walked out to the soft mud, you notice a small puddle, in the bottom of which there is a hole of some depth; into this you thrust your naked foot (not flinching if a crab "nips" you) and then pushing down your hands on each side of the small mound until you can get no further, you then turn over the mud and find the lug in the piece of mud removed. The use of putting the foot into the puddle is to prevent the animal from backing into another hole communicating with the water. When taken they are carefully washed and placed in a basin till wanted, when the hook is inserted at the head and run down to the middle, where it is brought out and inserted two or three times, twisting up the tail so as to leave none hanging from the hook. This is a very unpleasant operation, not only for the worm, but for the operator, as a nasty, yellow, slimy liquid exudes from the worm and stains the hands, but, notwithstanding this, the lug is a most valuable bait.

The Pollock, or mud-worm … This is one of the chief baits used by fishermen. It is usually found by digging with the hands or else with strong iron forks in the mud of the estuaries or creeks that run up from the sea. It is occasionally found under stones or old timber which has been long in one position. The abode of these insects is easily ascertained from the mud casts which they make above their dwelling. Boys are usually employed to collect or dig them and it is amusing to observe the rapidity with which they thrust their hands into the mud, turn over the mass, and extract the worm without injuring it, placing it in any old tin pot or earthenware basin; but as soon as the tide returns, and they have done digging, they at once wash them perfectly clean and put them in a broad flat box, known by the name of the "bait box" … A little fresh sea water must be put to them each day, the dirt removed, and the stale water poured away; the box should be kept in a cool place, and, if carefully attended to, the worms will keep for a long time. In baiting with the pollock-worm it is usual to place a couple on the lid of the bait box and then run the hook through the necks just at the back of the head, letting the worm dangle at its full length from the hook. This bait can be used in any way, either at anchor or whiffing. The worms are generally sold by the diggers at from 3d. to 6d. per pint, which is usually enough for one or two days' fishing.

Angling in Salt Water: A Practical Work on Sea Fishing with Rod and Line from the Shore, Piers, Jetties, Rocks and from Boats (1887) John Bickerdyke at pages 38, 39 & 40

… Fisher boys will generally dig lugs in the shore and ragworms in the harbour mud for a consideration.

Lugworms

… are excellent baits for most ground-feeding fish, but are unpleasant to fish with, having a fluid interior, which runs out at the slightest provocation. They may be used whole or in pieces. They are from 4in to 6in in length, and may be easily found by digging deeply with a spade in the sand where worm casts are noticed. Whiting, codling, and flat fish take these worms greedily, and, as a matter of fact, they are good all-round baits. To keep lugworms, place them in a bucket of water with sand. Change the water daily. They can also be dried on a line if their fluid interior is squeezed out. The thin end of the worm containing sand is not usually placed on the hook, though fish will take it.

"The book of the all-round angler: a comprehensive treatise on angling in both fresh and salt water" (1888) John Bickerdyke at pages 39 & 40 (Division IV)

Chapter III: Baits

Lugworms

… are excellent baits for most ground-feeding fish but are unpleasant to fish with, having a fluid interior, which runs out at the slightest provocation, on which account they should be used whole. They are from 4in. to 6in. in length, and may be easily found by digging with a garden fork in the sand where worm casts are noticed. Whiting and whiting pout take these worms greedily, and, as a matter of fact, they are good baits for most sea fish. To keep lugworms, place them in a heap of wet sand and seaweed, in a cellar or other cool place.

"The Sea and the Rod" (1892) Deputy Surgeon-General Charles Thomas Paske & Frederick George Aflalo at page 153

Chapter XVII

Concerning Baits

1. Worms

The name Lugworm is used only in common parlance; it is known to naturalists, however, by the very appropriate name of Arenicola piscatorum. And indeed, however objectionable it may be to handle, especially when impaled on the hook; and however the stains of the yellow fluid, which it exudes when bruised, may offend the eye, or its smell assail another of the angler's organs, it certainly is a prime favourite with nine sea fish out of every ten, and the angler who has a good pailful of lugs may generally rely on having good sport with cod and codlings, whiting, mackerel, and pout.

Unlike lobworms, they soon deteriorate, unless very constantly looked after, and should be kept in a cool, dark place in wet sand, the dead ones being frequently sorted out and thrown away. Few objects are there so disgusting as a defunct lug, in which state it repulses even the fish.

"The Badminton Library: Modern Sea Fishing" (1895) John Bickerdyke at pages 94 & 95

Lugworms

Lugworms, which are sometimes, but rarely, called lobworms, take the highest rank among baits for sea fish. They are dark reddish-brown in colour … They exude a nasty yellow fluid which stains the fingers, and the narrow end of them, which should be nipped off, contains little else than sand. A lugworm lives in sand, through which it eats its way, extracting any available nutriment, and throwing up above the surface the sand which has passed through its alimentary canal. It often grows three or four times as large as the dew or lobworm of our gardens.

Lugs are obtained without much difficulty by digging wherever the casts are noticed; but be very smart in pouncing upon them when they are thrown up, for they bury themselves in the sand with great rapidity. Mr. Wilcocks has stated that these baits must never be cut, because the liquid interior itself runs out, leaving nothing but the empty skin; but, as I have said, the sandy end is nearly always pinched off by the fishermen in the manner I have directed. Lugworms can be kept for some time in a cool place in a box of wet sand or seaweed, but it is very necessary to look them over daily, for a dead one left among them for a few hours turns putrid and quickly kills the rest. These baits are so killing for bottom-feeding fish that it is quite worth while going to some expense to obtain them; and if they are not found in the district where one may happen to be fishing, it is good policy to send a telegram or letter to the nearest part of the coast whence they may be obtained by parcels post or otherwise.

While this book was in the press I received the following interesting notes concerning lugworms from Mr. Edward Hanger, of Deal. "There are two kinds of lug here, one the large yellow-tail lug, so-called by our fishermen, and the other the ordinary or common black lug. The yellow-tail will keep alive much longer than the common lug, and is the best for bait for whiting and cod. The common lug is best for all kinds of flat fish, because the large lug will choke small hooks up. The yellow-tailed lugs are very difficult to dig up, as they generally lie well down into the sand. When rough and cold weather sets in the fishermen sometimes squeeze the inside out from the tail up through its mouth and then hang them over a line, and by this means a man has bait when the weather breaks up."

"Practical Letters to Young Sea Fishers" (1898) John Bickerdyke at pages 95, 96, 100, 101 & 168

Natural Baits and How to Find Them

Our principal sources of bait supply are, in a seaport town, the shell fish shops, which will usually be found hidden up some back street. Here we may expect to find mussels, cheap oysters, cockles, winkles, whelks, and shrimps. Wherever amateur sea fishing is largely carried on, the proprietor of the shop will probably arrange for a supply of lug, and rag worms. The little bare-footed lads who are running about the quay, anxious to earn a few pence, are often able to dig worms in the sand, or in the mud of the estuary.

Lug Worms

Lug worms, sometimes called lob worms, but not to be confounded with the earth worm of that name, vary in colour from almost black to a light brown, or drab. They also vary greatly in size, according, probably, to their age, being mostly a little larger, or rather fatter than a lob worm of the earth. They consist of little more than a skin containing a nasty yellow fluid, except that at the tail end, which is much thinner than the rest of the body, their skin usually contains nothing but sand. This portion should be nipped off, but fish will take it, and it should be husbanded when we are short of bait. They are horrid baits to use owing to their liquid interiors.

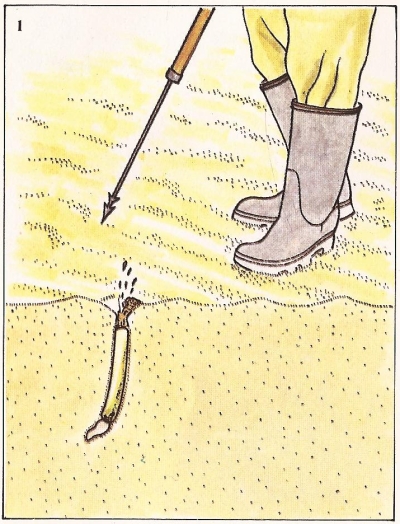

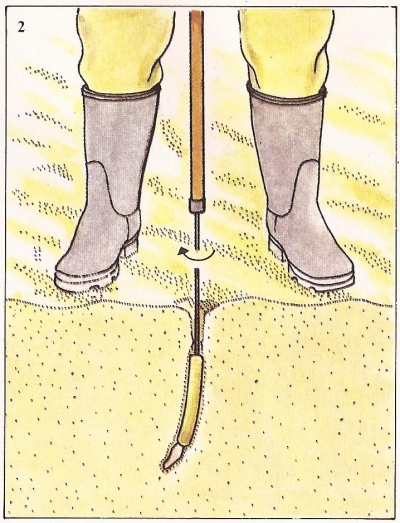

Lug worms are easily caught where the soil is not too hard to dig. The way to catch them is to walk very quietly up to one of the worm casts, which are usually so numerous on the sandy shore, stick a spade as rapidly as possible in a perpendicular position about 5in or 6in from the cast, and with all possible speed throw up a spadeful of sand. The track of the worm can usually be seen right down through the sand, and the worm itself seen if the digger has been quiet and adroit. The worm hole usually goes beyond the depth to which a spade can be forced, and if the worm is alarmed it will retreat to the bottom of its hole, out of reach. The chief art, therefore, in getting these baits is to get in the spade and throw up the sand before the worm has time to make good its retreat in the direction of the antipodes. I have kept lug worms for several days in a bucket of water, on the bottom of which was an inch or two of sand. The water should be changed daily, and the dead worms picked out.

Mr. Edward Hanger, a well-known Deal boatman, informed me that in his locality there are two kinds of lug worms - a large yellow tailed lug which will keep better than the common lug, and is the best bait for whiting and cod, flat fish preferring the common lug. The yellow tailed fellows are sometimes dried by being hung over a line, their liquid interior being first squeezed out through their mouths.

Bottom Fishing from Boats

… for fishing near the bottom there are, as a rule, no better baits then lug worms, mussels, rag worms, live shrimps, and herring. Their merits vary on different parts of the coast, but, speaking generally, I should class them in about the order given.

"Dover as a Sea-Angling Centre" (1900) Deputy Surgeon-General Charles Thomas Paske at pages 20 & 21

Chapter III

A third variety still more used by all sorts and conditions of men and boys is the sand worm. These are the creatures which dot the sandy bed with "casts" at low water; marvellously abundant in some places, but not in the immediate vicinity of Dover owing to its shingly beach. It might appear a very easy task to dig them up with a spade or pronged fork, but when reduced to practice it is by no means so much so as at first sight appears, for unless approached with caution and the weapon inserted with considerable speed and dexterity, the chances are that down they will have dived to some unknown depth. To many anglers - myself amongst the number - the great objection to their use consists in the plentiful supply of a bright yellow, ill-smelling fluid which oozes out on the smallest provocation. Fingers become dyed that colour in consequence, not easy to remove. The best worm of this kind comes over from Calais, and during the season, the traffic becomes considerable.

"Modern Sea Angling" (1921) Francis Dyke Holcombe at pages 9 & 10

Introductory

… But the amateur should always be ready, if necessary, to obtain his own bait. There are men who would consider it infra dig (no pun is intended!) to dig their own lugworm, which is a staple bait, of course, for many kinds of fish. This is an attitude which it is difficult to understand, for the digging of lugworm has a fascination all its own, in addition to being remarkably good, if rather back-aching, exercise. To the allotment holder, at any rate - and there are a good many such in these days - it should present no terrors.

"Modern Sea Fishing" (1937) Eric Cooper at pages 49 & 50

Shore Fishing

Lugworm

The most valuable food for almost all species of fish is found everywhere around our coasts where there is a sand shore …

In digging for lug, do not make the business unnecessarily strenuous for yourself by using a spade. A fork is the proper implement, for not only is less energy required, but the worms are not cut to pieces as is the case with the spade. Any worms that should be damaged must be kept separate from those that are whole.

Do not put the fork under the first worm-cast you come across. The worm is not in this patch of sand at all. The cast shows where it entered the sand but it is now lying, perhaps a foot below the surface, a short distance away. A close examination of the ground will show small circular hollows; underneath these are the heads of the worms; and here are the spots where you should dig … Provided you can get a good supply of worms and are not dependent for your fishing on using every scrap of worm you possess, pinch off the thin tail part; it is mostly composed of sand and is of little use as bait.

Lug will keep alive for some time in a shallow box lined with pitch or in a piece of dry sacking. If you use a box see that it is fitted with a lid; rain will quickly kill them. Examine your worms daily and weed out those that may have died.

In some localities - Dungeness is one such place - a very similar worm, but darker in appearance and only found near or at low-water mark, is a particularly good bait for plaice.

Do not, when using lug, be sparing with the amount you put on the hook. You can either make a bunch of them, using two or three, or a single good specimen may be threaded on the hook so as to leave a piece trailing behind.

"Sea-Fishing from the Shore" (1940) A. R. Harris Cass M.B.E. at pages 44 & 45

Chapter IV

Bait

The next bait in order of merit, (after crab) in my opinion, is the lug-worm. On a sandy shore you may expect to find these … Although this form of bait may be used anywhere, and at any time, it is most deadly when tried on a sandy beach, as it is the natural food of foraging fish in that area.

An excellent way to keep lug-worms alive for several days is to place them, as you dig them, in a tin containing dry sand, but, even when actually fishing, see that the tin is not in the glare of the sun: a cool shady place is the ideal one. Of course, use a perforated cover so that air can enter the tin. When the lug-worm is freshly dug it is full of fluid, but, like lob-worms kept in damp moss, it improves and hardens with its exile in the dry sand.

"Approach to Angling in Fresh and Sea-Water" (1950) E. Marshall-Hardy and Lieut. N. Vaughan Olver, R.N.V.S.R. at pages 187 & 188

Section IV: Sea Fishing from Jetty, Pier or Shore

Chapter II

Baits and where they are found

… Now let us make for the sandy foreshore below highwater mark, where if you are a youngster under 70 you will enjoy digging for lugworms.

Lugworms

These worms, which may be as thick as your finger, grow to a length of some 8 inches and are black or golden red in colour. They exude a harmless fluid which will stain your fingers yellow. Lugworms make a U-shaped burrow in the sand up to 2 feet in depth, throwing small whorls of sand to the surface as they pass it through their bodies to obtain nutriment. These bristly creatures are excellent bait for all bottom-feeding fish.

You will notice that they appear to live in colonies, whole stretches of sand showing no sign of them, while other sandy areas are strewn with their tell-tale casts. Mark these stretches well, for these are the places where fish can be expected to feed.

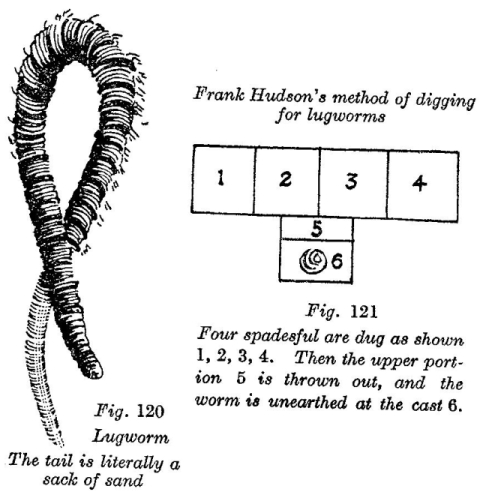

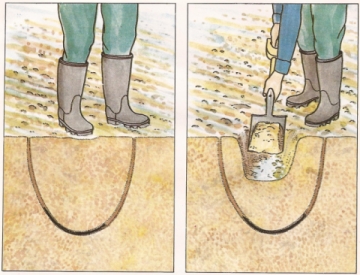

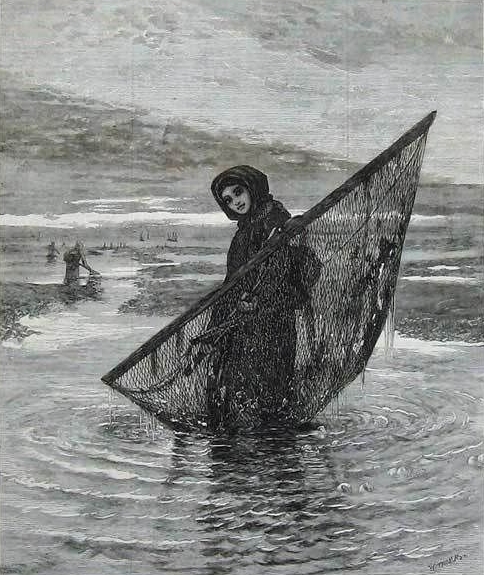

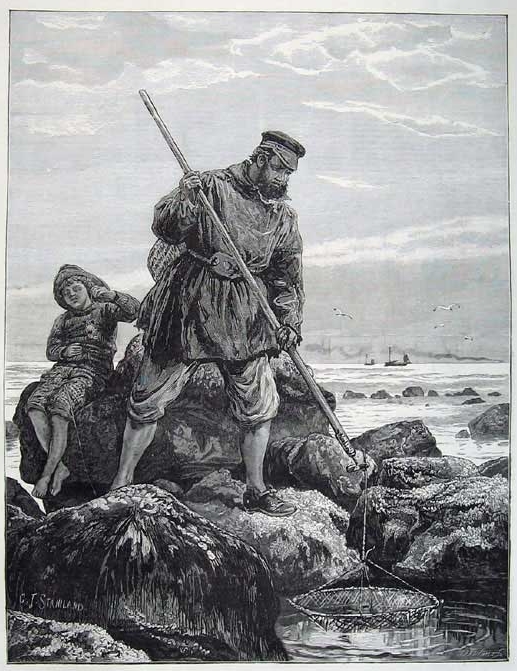

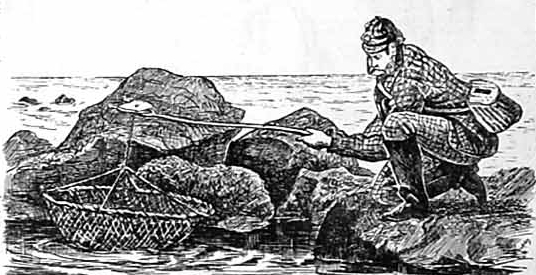

Unless you dig properly for lug your energies may well be fruitless. Glance at the illustration which shows a really productive method of digging for them. Put a couple of dozen worms into your wooden box; they will be sufficient for your immediate needs.

"The Modern Sea Angler" (1958) Hugh Stoker at page 37

Chapter Three

Baits

A. Worm Baits

Lugworm

… In Kent, and possibly elsewhere, large lugworm are preserved by squeezing out the pulp and then drying them on a line. The finished product, which has been likened to tobacco twist, is sold in some tackle shops around the south-east coast. It is an effective bait, and much cleaner to handle than the live worm.

"Sea Angling" (1965) Derek Fletcher at pages 145, 156, 230 & 231

Chapter 15: Baits and Where to Find Them

A word of warning is necessary, particularly to those to whom bait-digging will be a new venture. You should not mix ragworm and lugworm together in the same box. The ragworm will usually kill the others and make them useless as bait. Although both worms can be dug in the same area, nature has placed the natural haunt of the lugworm near the surface, while the ragworm lives lower down.

Although ther are deaf, the haul of worms will not be so great if you go about digging operations with too much noise. They are extremely sensitive to vibration and, for this reason, the worm casts must be approached quietly. Worm casts are small holes in the surface mud. Naturally, the greater number of holes the more numerous the worms. Drive the fork perpendicularly about 6in away from the cast. Then throw up a pile of sand or mud, when you will see the worm-track. If you have been quick and quiet enough you will see the worm itself. The right technique of digging is to get in the fork throwing up the sand before the worm is alarmed and able to retreat into the depths.

Small wooden boxes are best for keeping lugworm in after you have dug them. A little seaweed and sand is excellent for keeping bait fresh and lively for several days. In collecting the worms for keeping, care should be taken to put in the box only the uninjured. One or two half-worms will soon disturb the keeping qualities of the others.

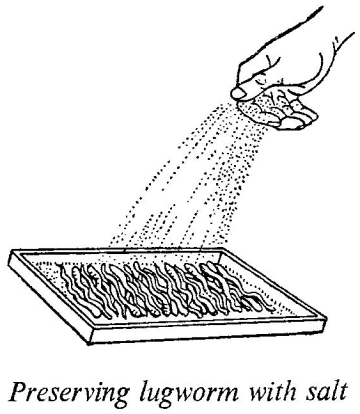

Good results have been had with preserved lugworms. One method of preserving, and there are several, is to cover a small box with an inch layer of salt. Worms should be put on the salt and covered with another inch layer. Put in a dry place they will keep for a long period. A point to be remembered is that the worms must be salted on the day that they are dug. It is not necessary to remove the fluid.

Chapter 17: Coastal Survey

On the mouth of the River Stour, this is a great centre of both freshwater and sea-fishing. Sandwich Bay is about 1½ miles from Sandwich itself, and the river end of the bay is usually the best. Flat-fish can be had in most months, bass and silver eels in the summer; codling, whiting and pouting in the winter.

… The bait is mainly lugworm, but cockles and mussels can be used. Yellow-tail lugworm are found in the centre beaches of the bay, with common lug near the river mouth. The yellow-tail is the largest and best bait for the East Kent coast and bait diggers come from neighbouring towns.

"Pelham Manual for Sea Anglers" (1969) Derek Fletcher at page 69

Lugworm

… Keep them in a wooden box with a little sand and seaweed. Make sure no half-worms or squashed ones are mixed with good specimens or the keeping quality will be affected. Never mix them with ragworm or the result will be a soggy mass.

Lugworm can be preserved and make useful baits. Cover the bottom of a shallow box with a layer of salt. Lay the worms on top of this and cover with another layer of salt, about an inch thick. Store in a dry, cool outhouse away from the sun. Use only freshly dug worms and it is not necessary to roll out the fluids as is often practised.

"Cod Fishing" (1978) Bob Gledhill at pages 48, 56 & 57

Baits

If you can't get down to the beach to get your own bait and have to rely on a bought supply, I recommend you to fix up a private deal with a professional supplier rather than rely on your local tackle shop having something. I know several groups of anglers who live well inland and operate a scheme like this for themselves, and they are never without good bait.

The way to go about it is to go to a beach where you know there are plenty of worms to be dug and ask around at low water, looking for those diggers with the brimming buckets. You'll have to be polite and discreet and convince the digger you aren't from the Inland Revenue, but it shouldn't be too difficult to find a digger prepared to supply you on a regular basis.

You may be expected to pay more to the digger than he gets from the shop, but even if you pay normal retail price at least you know the supply is regular and good. It will also involve you picking the worms up rather than having them delivered and you must certainly never back off on an order. If you live so far from the sea that even picking them up is impractical, then watch the classified coulmns of the angling press and pick yourself a wholesale supplier from there. You will have to pay for carriage charges, but again the supply should be reliable.

Lugworm

Lugworm catches more cod than any other bait. That is an inescapable fact of fishing because so many anglers use nothing else for cod fishing. The popularity of lugworm stems from several reasons. Firstly, there are few places where lug will not catch cod. Secondly, it is the most readily available of baits, being present on beaches right round the British Isles. Thirdly, it will keep for a considerable length of time. With three powerful reasons like that it is no wonder that for many anglers cod bait means just one thing - lugworm.

I mentioned a while back that I advocate bulk-buying syndicates for those with fresh bait problems, and I had lugworm in mind when I said that. But for those who prefer to dig their own, here's how to go about it.

Unless the lug are so spread out that digging a trench for them would give an uneconomic return - in which case I would either find a better worm bed or use a narrow spade to dig them out individually - a garden fork is the ideal tool. The best type of garden fork is a large one, capable of going deep when the worms are deep. And if you are buying a new one, look for the flat-pronged variety, sometimes referred to as a potato fork.

Locating a good lugworm bed isn't something I can write much about. Either keep your eyes open when you are fishing or ask around. To start trenching I look for a patch of casts close together, then score out the path I want to take on the surface of the sand with the fork. I usually work no wider than two forks because of the problem of flooding. Don't try and slice too much sand out at once or worms may be completely encased in the clods of sand and missed. If your trench floods, narrow the trench, if it's dry, you can go out to three or four forks wide.

If you plan to use the lug within a day or two there is little work that needs to be done to the bait other than spreading it out on a sheet of newspaper and covering it with more newspaper. Keep it as cool as possible. In summer - though I rarely use lug in summer for cod, preferring peeler crab - I keep the lug in my bait fridge. In winter the air temperature is cold enough in the garage.

If you want to keep lug longer than a couple of days, you can keep them alive for weeks by using a big tub and an aerator. I was shown this method of keeping lug by pals on Tyneside and the local record up there is three months. You have to use unpunctured worms and start off with clean seawater, but one aerator will look after a lot of lugworms. I tried the method myself to be certain it worked before including it in this book, though I have no need of it as there are millions of lug at the end of the road.

Opinions differ on the best method of hooking lug. Some head first, some tail first. Some throw the sandy tails away, some try to stop the worm bursting and some want it to burst to spread the juice downtide. I don't think it makes a scrap of difference how you hook a lug.

How many to put on the hook? It depends on the size of your lug. On a big tide I can dig the big black lug on my home beach, and they are up to ten inches long each, so half of one is a big bait. It's easier not to talk in terms of numbers on a hook, but how far up the shank and the line the worms should go, and I like to keep pushing lug on the hook until there is between one and two inches of worm above the eye of the hook (and, of course, worm covering the hook iteslf). I always leave the hook point clear on all baits.

"Fisherman's Handbook" The Marshall Cavendish Volume 2, Part 34 (1978) Ron Edwards at pages 950 to 952

Bait

Lugworm

The lugworm, Arenicola marina, is one of the most popular of all baits used in sea angling, particularly with anglers fishing the East Anglian and Kent coasts. It is a smaller species than that other very popular choice of sea anglers, the King Ragworm, but when used from beach or boat it can be one of the deadliest baits for cod.

Ninety per cent of the sea fish found around the British Isles will usually take this bait readily, and besides being ideal for cod, it is particularly useful for the smaller varieties of flatfish - plaice, dabs and flounders. Many inland sea anglers prefer to buy a day's supply of lugworm from their local tackle shop, but anybody can dig an adequate supply for himself.

The best environment

The lugworm prefers sheltered beaches with a good depth of top sand and where the sea has a low salinity. River estuaries, therefore, provide the best environment. One never has to travel far along the British coastline to encounter such habitats - Whitstable, Dale Fort, St Andrews, Millport, the south coast of the Isle of Man, Clew Bay on the West Coast of Ireland, are just a few of the many well-known areas where the lugworm can be dug in numbers. Size and colouring can vary considerably from area to area - in some cases there is a marked difference between the worms dug from the same sandy bay - due to environmental factors.

The common lugworm is often known as the 'blow' lug to differentiate it from the black lug which is very thick-skinned and requires gutting to prolong the time it will keep, and from the Deal yellow-tail, a worm peculiar to the south side of the Stour Estuary in Kent.

Lugworm live in a U-shaped burrow in the sand, the entrances of which are marked at one end by the tell-tale spiral casts and at the other by a depression in the sand known as the blow hole, through which the worm draws its food. Into the tunnel fall particles of sand mixed with water and organic matter, all of which the worm eats. The organic matter is digested and the sand is excreted, forming the cast at the other end of the burrow.

For digging the common lugworm the ordinary flat-tined potato fork is the best tool; a spade chops too many worms in half. Lugworm casts are found on any sandy beach below high water mark but, normally, the nearer to the extreme low water mark the greater the number of casts to be found and the bigger the worms. If the sand is covered in casts no more than 2 or 3 in apart, then worms can be dug by trenching, that is, digging the sand as one would the garden. However, if signs are few and far between, 'singling' is best. This involves removing the sand between the blow hole and the cast, thus uncovering the worm after about three forkfuls. The burrow is lined with mucus from the worm's body, giving it a bright orange colour rather like rust, and enabling the angler to see exactly which way the burrow is running at each forkful.

The worms should be removed to a clean wooden box or plastic bucket. Never use a galvanized pail as the zinc kills the worm very quickly. When sufficient worms have been dug, they should be washed in clean sea water to remove all particles of sand as well as any worms pierced by the fork. These should be put into a separate container for, although they will live as long as the whole worms, the blood exuded by their wounds has an adverse effect on the others.

Storing lugworm

When you return home, the worms should be placed on clean, dry newspaper in a single layer, with another piece laid on top so that the bait is sandwiched between two sheets of paper. If the weather is cold, the temperature not rising above 4.4°C (40°F), and the worms are stored in a garage or outhouse, they will stay in good condition for 4-5 days. In the summer, when temperatures are high, this life is reduced to less than 36 hours unless the worms are refrigerated. Another method of keeping worms alive until required is to place them in a well-aerated saltwater-filled aquarium. With this method care must be taken to remove any dead worms immediately, before they can pollute the water.

Unfortunately, the peak of autumn cod fishing coincides with the time when lugworm is most difficult to obtain, for it is spawning. Although the actual day it occurs varies from colony to colony, in nearly all areas spawning takes place between the last week of September and the middle of November. Lugworms are not hermaphrodite (having characteristics of both sexes) but sexed male and female. The eggs of the females and the sperms of the males begin to accumulate from mid-summer onwards, moving around in the body fluid and giving the worms a milky appearance. If a worm is broken this fluid will be found to be rather sticky and slimy.

When the worms are ripe, the spawn of both sexes is released onto the sand, where fertilization occurs. If the worm survives the spawning it will go right to the bottom of its burrow and remain immobile for two or three weeks while it recovers. During this period it eats very little, creating no tell-tale casts to mark its presence, so that sands that previously appeared to contain millions of worms, now seem completely barren.

Four or five days after spawning, the larva hatches. About 1/100 in long, it is pear-shaped, opaque, and bears no resemblance to the adult worm. By early spring it has taken the form of the adult and is found high in the sand, working its way downwards as it matures. At two years old it spawns for the first time and usually lives to spawn a second time, at three years, but after this the lug dies.

The Deal yellow-tail

There is evidence that adult lugworm will come out of the sand and swim freely in the sea. This phenomenon usually occurs in the early spring. The Deal yellow-tail is probably a sub-species of Arenicola marina, although many authorities believe it to appear different simply through environmental factors. However, the worm behaves entirely differently from the common lugworm. The cast, instead of being a haphazard spiral, is perfectly symmetrical, and the worm burrows to a greater depth than the common lug.

The yellow-tail is generally larger, and when dug appears very limp, seeming, to the uninitiated, to be dead. It also has the peculiar habit of coiling itself into a circle when held in the palm of the hand, whereas the common lug will only bend slightly. The best way of keeping the yellow-tail - its name derives from the bright yellow stain it leaves on the hands - is in clean sea water.

Another sub-species is the black lug, which is even bigger than the Deal yellow-tail and has a very thick skin. It often lives in a mixture of mud and sand, where the most successful way of obtaining it is to use a small, long-handled spade, digging straight down from the cast and following the trail until the worm is sighted. It is rarely possible to trench for this worm.

Roll them in newspaper

Immediately after digging, the intestines and blood should be squeezed out through the head end and, to keep them in perfect condition, the worms should be rolled singly in sheets of newspaper. The black lug is large enough to provide several small baits from a single worm, although for cod fishing a whole worm should be threaded on the hook. Because it is tough, it makes an ideal bait for beachcasting.

Common lug can be threaded either singly or doubly, depending on size, when beach fishing for cod, but for boat fishing it is usually better to hang them from the bend of the hook, just passing the hook in and out of the body where the sandy tail section joins the fat part. The number of worms put on a hook depends, first, on the size of the worm and, second, on the size of the fish expected. When fishing for varieties of small flatfish, a largish worm may be broken in half to provide ample bait for a small mouth.

"The Bait Book" (1979) Ted Lamb at pages 134 to 138

25 Lugworms

Lugworms occur most frequently in muddy ground (Fig 48), and in mixtures of sand and mud. They can tolerate brackish as well as salty water, and this makes estuary flats about the best collecting grounds. The worms vary a good deal in size - from 1½in to almost 1ft - and in colour, ranging from light red to brown or slaty black. Their bodies are in two sections; a fleshy, pulp-filled head and stomach extends for about two thirds of the total length, and a thin, tube-like tail, which is usually filled with sand that has passed through the digestion system, constitutes the rest.

The worms usually live in U-shaped burrows, extending from 1 - 3ft below the mud surface. The worm moves its head up one shaft, which has a funnel-like opening variously called a 'dimple', 'dupple' or 'shoot', while the tide is in. Here it takes in food particles along with the sand, water, grit and mud which drift into the opening. When the tide falls the worm retreats to push its tail up the other shaft, throwing out the inedible parts of its food in the form of squiggly little piles (casts) of sand or grit. When digging you will find that burrows with the head and tail widest apart will usually house the biggest worms.

In some instances the worms inhabit straight, deep, single burrows, and this happens most frequently in very soft ooze where the worm can easily reverse itself for excretory purposes. The worms move in their burrows with the help of the hair-like tufts spaced along their bodies. They rarely leave the burrows, and even breed by extending only a part of the body from the head hole to cast out eggs and milt.

Keeping

Fresh lugworms rarely keep alive for more than three days, and by the end of that time they look a bit the worse for wear. They should not be kept in anything damp, because they will merely absorb water and die all the more quickly. Instead, wrap them in dry newspaper, lying the worms across a strip so that they are kept apart and then rolling the strip up into a coil that can be secured with a rubber band.

There are quite a few ways of preserving lug, but none of these baits are quite so attractive as fresh worms, and it is always useful to perk them up before use by dipping them in pilchard oil.

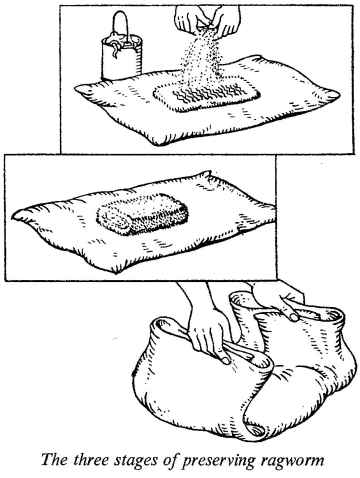

All the methods demand that the worm should be gutted, leaving only the rubbery outer body. To do this you hold the lower part of the worm firmly between thumb and finger, and with the other hand take the same grip just above your hold. Then squeeze, and push towards the head of the worm as if you were squeezing a drinking straw to push out the water. Discard the guts, and break off the sand filled tail which generally will not last. Now the gutted worms can be dried, frozen or salted.

To dry them, thread the gutted bodies, not touching, onto some fine fishing line, and then hang them up like a string of washing in a dry, well aired room - a garden shed or conservatory is ideal. The bodies will shrivel and harden at which point they can be taken down and sealed in small plastic bags. In use, they swell on contact with sea water to take on some of their original form.

For freezing, lay the worms out separately on a piece of paper in the coldest part of the freezer. Once hard, put them in collections of a dozen or so into small plastic bags, and then return them to the freezer (a fridge ice box will do as well).

For salting, put a ½in layer of coarse salt in the bottom of a wooden or plastic container, lay the worms out on this and cover with another layer of salt. If you have a lot of worms you can go on repeating this until the box is filled, ending with a salt topping. They can also be preserved in a jar of strong brine, but I find they become too soft with this treatment. Incidentally, gutted lugworm, wrapped in newspaper and kept in a cool place, will last for a week or more.

Uses

Whole large lugworm are good baits for cod, pollack, bass and rays. A collection of smaller lug on a large hook will also make a presentable bait for these species. Smaller lug, used individually, are superb flatfish baits, taking flounders, plaice, dabs and sole. Small pieces of larger worms are also useful in this area.

Lug lends itself well to combination baits, and it is particularly good as a bait for attaching to a flashing or spinning lure. The traditional flounder rig, with a smallish hook (8 - 4) trailing on a trace of 3 to 7in behind the spoon, is usually baited with lug. Incidentally, flounders are not the only flatfish to respond to the baited spoon technique - plaice are often taken on this rig, and so are the larger brill and turbot.

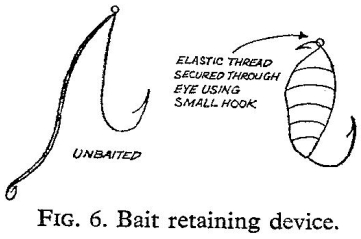

In beach casting, lug is often too soft to withstand a hearty cast without flying off the hook, and here it helps to 'tip' the worm-baited hook with a portion of some tough bait like squid or fresh mackerel, cushioning the worm and keeping it intact throughout the cast.

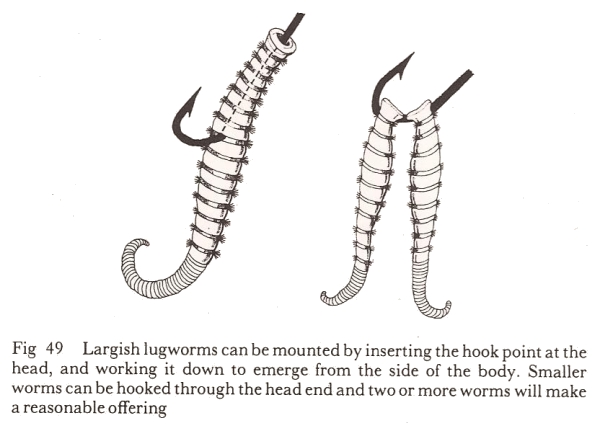

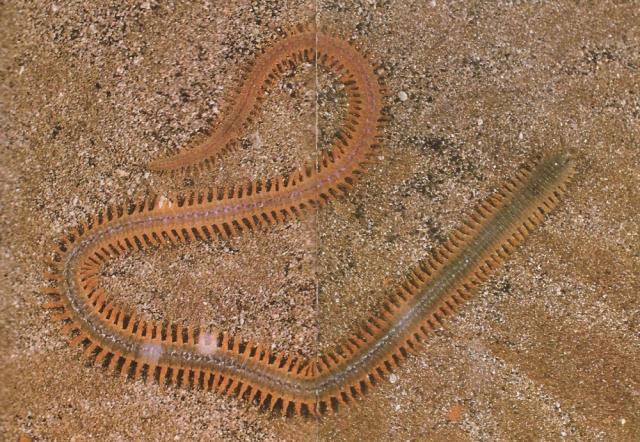

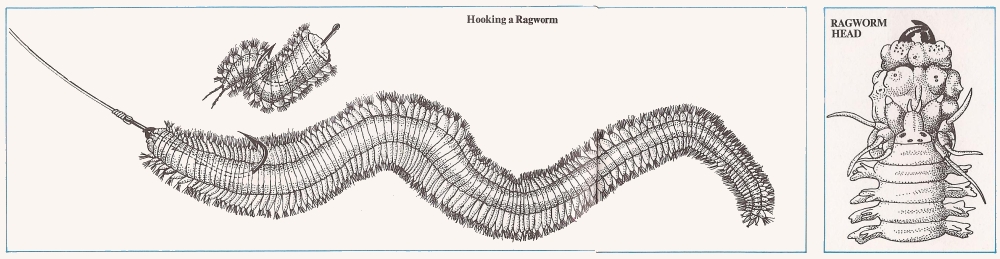

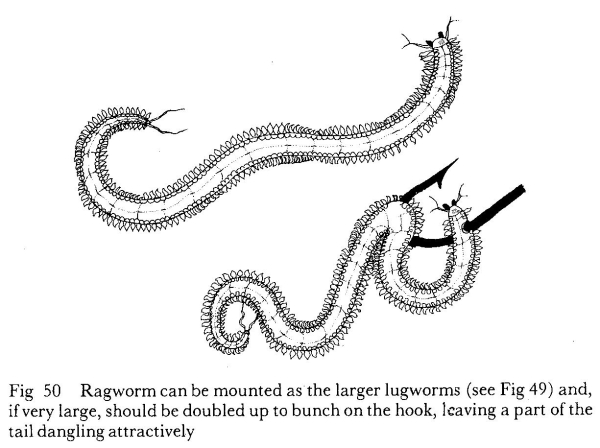

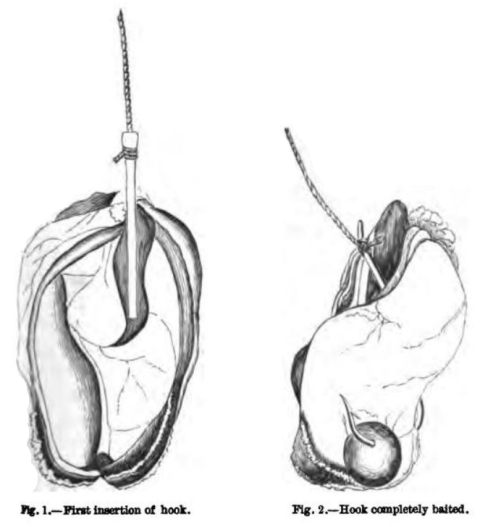

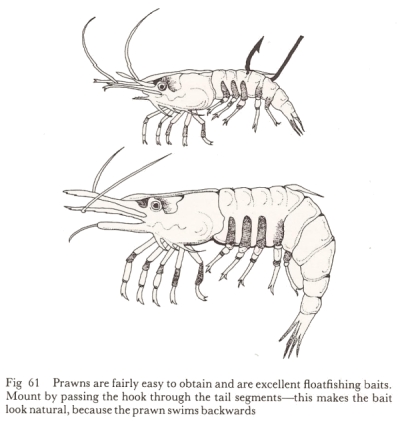

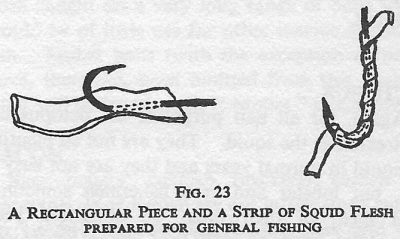

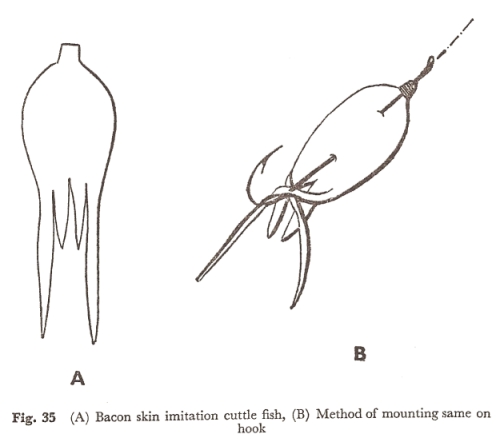

Presentation